Postpartum Depression and the Continuity of Prenatal Care in Florida’s Rural Spaces.

Project Summary

Florida has seen a 48 percent increase in hospital admissions and emergency room visits for postpartum depression (PPD) between 2006 and 2011.i When left undiagnosed and untreated, perinatal mood disorders like PPD can be incredibly harmful to both the parent and the child. Reportedly, depressed mothers experience debilitating symptoms that make it difficult to parent, including inadequate sleep, depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness, and low energy. These parents are also less likely to fully engage in their child's social, emotional, and physical development,ii which research suggests has a long-term effect on their well-being.iii

Mothers with untreated depression can develop a long-term struggle with this condition, which increases their likelihood of developing a stroke, cardiovascular disease, and type-2 diabetes.iv Researchers report that the risk of physical and behavioral consequences is related to the severity of maternal depression and contend that appropriate screening and treatment are helpful tools to reduce the prevalence and consequences of postpartum depression.v However, not all mothers receive the screening and medical care they need, especially poor and young women of color.vi

Research offers several reasons why mothers fail to obtain the necessary medical screenings and treatment for postpartum depression. One reason involves the mother’s healthcare utilization practices. For instance, many women who attend appointments to establish public benefits do not return for follow-up care after childbirth. This population is also not likely to sign up for maternal-child home visits or be screened for postpartum depression. These trends are especially prevalent in low-resource rural spaces, like Gadsden, Florida's only predominately Black County.

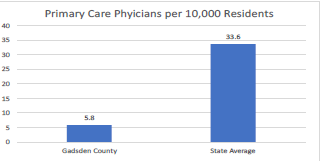

Figure 1

Not only are childbearing mothers in spaces like Gadsden County opting out of prenatal services, but mothers who wish to secure these supports also struggle to find primary physicians where they reside, as shown in Figure 1. Although maternal and perinatal services are available in Gadsden, this county is currently categorized as a Low Access to Maternity Care area, according to the March of Dimes Maternity Care Deserts 2022Report. This designation is given to counties with less than two hospitals and birth centers offering obstetric care, less than 60 obstetric providers per 10,000 births, and the proportion of women 18-64 without health insurance is greater than or equal to 10 percent. Similarly, Gadsden County has limited resources to address maternal mental health adequately, with only one mental health provider for every 720 residents.vii,viii

Inequities in maternal child health services and outcomes are not inevitable. With intentionality, progress can be made in closing these gaps. Often these disparities are seen in resource-starved communities undermined by benign neglect.ix Opportunities within these spaces are typically shaped by structured differences or systems that negatively impact development, like limited access to convenient and affordable medical care as well as health sustaining community assets such as quality grocery stores and clean public water.xi Another such system is structural or institutional racism, as noted in previous studies.xii,xii

Our team plans to contribute to existing scholarship and assist the challenge of reducing the prevalence of postpartum depression in Florida's rural spaces by identifying relevant social determinants of PPD and clarifying how healthcare utilization practices influence this condition's prevalence during the perinatal period. We aim to answer the following research questions with our empirical analysis: 1) What structural and demographic factors contribute to the prevalence of perinatal depression within Florida’s rural areas? and2) How does continuity of care trends influence PPD prevalence among this population?

Throughout the first year of the grant, we plan to pursue the following aims: 1) Identify variations in the prevalence of postpartum depression in Florida's rural areas, 2) develop a risk model for mothers who fall out of healthy start screenings in Gadsden County and examine how this decision is associated with PPD, 3) specify to what degree predictors for both outcomes (ppd; coc) are modified by socioeconomic status and structural racism, and 4) explore opportunities for community engagement that will help our team develop a sustainable approach to enhancing existing services available to mothers at-risk of or contending with postpartum depression.

Our interdisciplinary team plans to analyze a wide variety of quantitative and qualitative data and write at least two journal articles during the grant period. Our statistical analysis will rely on data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System(PRAMS) and Medicaid that we will secure via the IRB process. We intend to examine the health data graphically, calculate descriptive statistics, and compute distributions and bivariate analyses. We also plan to perform multivariate regression analyses to examine the associations between demographic (race, ethnicity, and class) and structural indicators.

For instance, in paper 1, we aim to determine the prevalence of postpartum depression and its determinants in Florida's rural spaces. With PRAMS data, we plan to utilize logistic regression to examine the associations between postpartum depression and demographic indicators while controlling for family characteristics (race, SES, and neighborhood deprivation status). In addition, we will test the impact of institutional/societal bias by utilizing the neighborhood deprivation indexxiv and other measures accounting for the effect of structural racism on health outcomes.xv

In paper 2, we plan to illustrate how lapses in prenatal care are distributed across Gadsden County. Our risk model, based on Medicaid data, will capture the mothers who opted not to participate in Health Start programs following birth. These mothers had an initial prenatal screening, but following childbirth, they did not elect to receive healthy start connection program services. We also aim to assess how falling out of care is associated with exposure to postpartum depression as well as other demographic (age, sex, race/ethnicity) and economic characteristics (median household income, etc.). Additionally, we intend to gather qualitative data through interviews and a focus group with healthcare providers and community interventionists who work with this population. The interview instrument will be designed to learn about the challenges of providing prenatal care, and postpartum depression supports to vulnerable mothers in low-resource areas like Gadsden County.

Finally, during the year supported by the planning grant, we intend to explore opportunities for a community intervention to help meet the medical needs of mothers at-risk of and/or contending with postpartum depression. We understand that several well-received programs currently provide community services to moms in the target area. Our first step in developing a community-engaged intervention involves an assessment of existing services that will help clarify gaps and identify opportunities to leverage long-standing relationships and create strategic partnerships. We intend to use findings from our statistical analysis and information gathered from the focus group, interviews, and meetings with providers and community interventionists to shape our approach(es) to expanding and developing existing supports. Subsequently, throughout the next few years after the grant period, we intend to scale up our empirical analysis. We also plan to pilot-test and fully implement our community intervention(s). We plan to write additional grants throughout the planning period to support this effort.

|

Katrinell M. Davis (PI) Sociology and African American Studies |

Kathryn Baughman Family Medicine and Rural Health, College of Medicine |

|

Joedrecka S. Brown Speights Family Medicine and Rural Health, College of Medicine |

Shermeeka Hogans-Mathews Family Medicine and Rural Health, College of Medicine |

|

Emem Kierian Family Medicine and Rural Health, College of Medicine |

Qiong (Joanna) Wu Human Development and Family Sciences |